- Year: 1984-1989

- 1984

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vestria

- 1985

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Corona

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vestria

- • Christmas on board M/T Vestria

- 1986

- • Aladdin is back to School after the Christmas holiday

- • Aladdin's adventure at Vinterspelen i Härnösand

- • Aladdin's adventure at Navigation School in Göteborg

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordic Link

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Tina

- • Aladdin's adventure in Helsingborg - November 1986

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Bellatrix

- 1987

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Ewaria

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Katarina

- • Aladdin's adventure at Roskilde Festivalen 1987

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Storön

- • Aladdin's adventure in Båstad and Mölle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nova

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Bleking

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Aurum

- 1988

- • Aladdin's adventure in West Berlin

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Lindfjord

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordanhav

- • Aladdin's adventure in SE Asia

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Autumn 1988

- • Christmas on board Nils Dacke

- 1989

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nils Dacke

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordic Stream

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Spring 1989

- • Aladdin taking down the Berlin Wall

- • Aladdin's adventure in Berlin - New Year 1989

- Year: 1990-1999

- 1990

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Spring 1990

- • Aladdin's adventure in Paris

- • Aladdin's adventure in New York

- • Aladdin's adventure in Amsterdam - Queen's day

- • Aladdin's adventure on board S/S Ingo

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bellona

- • Aladdin's adventure at The Wall concert in Berlin July 1990

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Westön

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsund

- 1991

- • Aladdin's adventure in Florida

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfjord

- • Aladdin's adventure in Amsterdam - Queen's day

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Eken

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Vingavåg

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord Nils Dacke

- 1992

- • Aladdin's adventure in Asia - India, Thailand and Japan

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Breant

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Artic 1

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bituma

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & India 1992 to 93

- 1993

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & Australia

- • Aladdin's adventure in a Norwegian jail

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Forsvik

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bituma

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok 1993

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & India 1992 to 93

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- 1994

- • Aladdin's Adventure in Thailand

- • Aladdin's trekking adventure in Nepal

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnhav

- 1995

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T United Polaris

- • Aladdin is moving to Bangkok

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margita

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Rankki

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Kaprifol

- 1996

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T Rankki

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - March 1996

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Argo Athena

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Summer/ Autumn 1996

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Argo Pallas

- 1997

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Songkran 1997

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ekturus

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Sun

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfjord

- • Aladdin in Stockholm/ His first internet experience

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Stolt Excellence

- 1998

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Winter 1998

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Asian Progress

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok and Mölle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Stena Barbados

- 1999

- • Aladdin's adventure in the Caribbean

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Alstern

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- Year: 2000-2009

- 2000

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfors

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsund

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Halmia

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- 2001

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Master Cody

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Nelly

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnsund

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnvik

- 2002

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvik

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsjö

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin buys his first digital camera

- • Christmas Horror Story

- • Aladdin's Christmas adventure in Go:teborg

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Fure Sun

- 2003

- • Aladdin's disappointment coming home to FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vinga Helena

- • Aladdin's adventure in Chiang Mai

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Anton

- 2004

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Sky

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Prospero

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cape Town, South Africa

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Jupiter

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's FIRE FIGHTING course in Göteborg

- • Aladdin moving in to his not yet ready condo

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Astoria

- 2005

- • Aladdin in Germany - How to obtain German licences

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T Astoria

- • Aladdin celebrating the summer 2005

- • Aladdin in Hamburg taking a course in German Shipping Legislation

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Pegasus

- 2006

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cairo, Egypt - April 2006

- • Aladdin at the DANGEROUS GOODS (IMDG) course

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Rainbow Warrior

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Jupiter

- • Aladdin's adventure in Rome and Thailand

- 2007

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Barcarolle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Marimba

- • Aladdin's first sick leave

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Barcarolle

- 2008

- • Aladdin's adventure in Los Angeles & Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Provider

- • Aladdin's holiday -Autumn 2008

- • Aladdin training at NTC in Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Promotion

- 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in Thailand - Malaysia - Gothenburg

- • Aladdin's FIRE FIGHTING course in Göteborg

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvåg

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - Summer 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in Seoul and Tepei

- • Aladdin is back FUNKY TOWN again - 2009

- • Aladdin on tour with Bangkok By Bike - October 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - October 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-River

- Year: 2010-2015

- 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Funky Town - March/ April 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure during Songkran in Bangkok - 2010

- • Aladdin's training at NTC in Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - April/ May 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Little Isan in Bangkok - May 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure during the Red Shirt protests - 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-River

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-Star

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - October 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Manila - November 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - November 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - December 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Phnom Penh - VISA RUN

- 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - January 2011

- • Aladdin's diving adventure in Pattaya - January 2011

- • Aladdin's Chinese New Year adventure in Bangkok

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - February 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- March 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in Vientiane, Laos - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ternvik

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- July 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- August 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cambodia - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board DE/T Randgrid

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club - September 2011

- • Aladdin's Advanced Fire Fighting course in Johor Bahru

- • Aladdin's Proficiency in Survival Craft & Rescue Boat course in Singapore

- • Aladdin's Advanced in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2011

- • Aladdin's escape to Pattaya during the flooding of Bangkok

- • Aladdin returns to a flooded Bangkok

- • Aladdin adventure in a flooded Bangkok - November 2011

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Maersk Cassandra

- 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Singapore - March 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - March 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure during Songkran in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Tokyo - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN again - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure at Rajadamnern Muay Thai Stadium - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure with Bangkok Photographers - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure at Thai Navy's shooting range - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Shanghai - VISA run - May 2012

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN again - June 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure with Bangkok Photographers at Benchasiri Park in BANGKOK

- • Hangover Man's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - June 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Maersk Claudia

- • Aladdin's adventure in Hong Kong

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - September 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2012

- • Aladdin's acupuncture adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure @ My Thai Language School in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin adventure in Siem Reap - VISA run - October 2012

- • Aladdin is back in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure at Faulty Towers: The Dining Experience in FUNKY TOWN/ BANGKOK

- • Fight night in Lao Khwan, Kanchanaburi, Thailand

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Mumbai/ Bombay - Advanced Medical Training - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Chennai/ Madras - DML & Para 16 Course - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure onboard Jet Airways flight to Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin is back home in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2012

- • Fight night in Thung Khok, Suphan Buri - December 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2012

- • Aladdin's last weekend in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN 2012?

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Britta Mærsk

- 2013

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN - March 2013

- • American girl in yet another Muay Thai fight - March 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Singapore - Visa Run - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok during Songkran - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure at Thai Navy's shooting range in Bangkok

- • Fight night at Rangsit International Boxing Stadium - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN/ Bangkok - May 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Richard Mærsk

- • Aladdin's adventure in Istanbul - August 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN/ Bangkok - August 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Birthday party in Thailand

- • Potluck in Bangkok

- • New Year in Singapore

- 2014

- • Aladdin buy new boxing gloves with the American girl - January 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Honolulu - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Asoke/ Sukhumvit intersection protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Ratchaprasong protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Silom/ Lumpini intersection protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Victory Monument intersection protest site - January 2014

- • Bridge Team Management course at Norwegian Training Center in Manila - January 2014

- • FRAMO course for Officers at Norwegian Training Center in Manila - February 2014

- • Going to Monk Ordination in Ban Chang, Rayong - February 2014

- • Monk Ordination in Thailand - February 2014

- • At Bangkok Wing Chun in Bang Na - February 2014

- • Last Night in Bangkok - March 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Voting for the EU Parliament - May 2014

- • Advanced Fire Fighting Course in Helsingborg - May 2014

- Skånsk Gästgiveri Tour - May 2014

- • Fire Fighting Course in Kalmar - May 2014

- • Falukorv - Thai Style - May 2014

- • Monk Ordination in Bang Pa In - June 2014

- Falukorv - Skåne Staajl - June 2014

- • Aladdin'n goes to the hospital - June 2014

- • Urban Safari “Hidden Gem” with Bangkok Photographers - June 2014

- • Visa run to Las Vegas - June 2014

- • Arriving to Las Vegas - June 2014

- • Hoover Dam - June 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure at Hangover Heaven - June 2014

- • Grand Canyon - June 2014

- • Aladdin's STOP OVER in Tokyo - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cha-am - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Tanzania - July 2014

- • Aladdin's African Safari adventure - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Zanzibar - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Aladdin's adventure in Skåne - October 2014

- • Aladdin going back home to Bangkok - October 2014

- • Halloween in Bangkok - October 2014

- • Aladdin's safari adventure in Africa - November 2014

- • The King's Birth Day/ Father's Day at Ratchadamnoen Road - 5th of December 2014

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #33 - Talat Rot Fai

- • December in Bangkok

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #34 - Tha Chalom

- • VISA run again - Aladdin's adventure on the Mekong River in Laos

- 2015

- • Aladdin flying back to Bangkok from Laos - January 2015

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Maersk Mediterranean at the TPP Terminal on Koh Sichang

- • Aladdin's safari adventure at Khao Yai National Park

- • Aladdin's Saturday night adventure in the Benjasiri Park in Bangkok

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #1 - Erawan Museum - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #2 - Coocking Thai Food - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #2 - Coocking Thai Food - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #3 - Royal Air Force Museum - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #4 - Rice Barge Cruise on Chao Phraya River - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #5 - Ayutthaya Cruise Tour - February '15

- • Thai Funeral at Wat Hua Lamphong (วัดหัวลำโพง) - February '15

- • Birthday party in Bangkok - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #6 - Siam Naramit Show - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #7 - At Camillian Hospital - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #8 - Museum of Siam - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #9 - Bangkok National Museum - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #10 - The National Museum of Royal Barges - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #11 - Ancient City - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #12 - Rock Around Asia Art Gallery - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #13 - Thai Labour Museum - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #14 - Chinese New Year in Bangkok China Town - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #15 - Asiatique The Riverfront - February '15

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #36 - Wat Salak Tai Community

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #16 - Chao Phraya Express Boat - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #17 - Koh Kret - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #18 - Temple tour with Chao Phraya Tourist Boat - March '15

- • Visa run to Poi Pet, Cambodia - March '15

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Romø Mærsk

- Search ship by name

- Alstern - 1999

- Argo Athena

- Argo Pallas

- Artic 1

- Asian Progress

- Astoria - 2004

- Astoria - 2005

- Aurum - 1987

- Brcarolle - 2007-1

- Barcarolle - 2007-2

- Bellatrix - 1986

- Bellona

- Bituma - 1992

- Bituma - 1993

- Bleking - 1987

- Breant

- Britta Mærsk - 2012

- Bro Anton - 2003

- Bro Jupiter - 2004

- Bro Jupiter - 2006

- Bro Nelly

- Bro Promotion - 2008

- Bro Provider - 2008

- Corona - 1985

- CT Sky - 2004

- CT Star - 2003

- CT Star - 2003

- CT Sun

- Eken

- Ek-River - 2009

- Ek-River - 2010

- M/T Ek-Star - 1210 -1

- Ek-Star - 2010 -2

- Ekturus

- Ewaria - 1987

- Forsvik

- Framnäs - 2003 -1

- Framnäs - 2003-2

- Framnäs - 2004

- Fure Sun - 2002

- Halmia - 2000

- Kaprifol

- Katarina - 1987

- Lindfjord - 1988

- Maersk Cassandra - 2011

- Maersk Claudia - 2012

- Margaron - 1993

- Margaron - 1994

- Margaron - 1995

- Margita

- Marimba - 2007

- Master Cody - 2001

- Nils Dacke - 1988

- Nils Dacke - 1989

- Nils Dacke - 1991

- Nordanhav - 1988

- Nordic Link - 1986

- Nordic Stream - 1991

- Nova - 1987

- Pegasus - 2005

- Prospero - 2004

- Rainbow Warrior - 2006

- Randgrid - 2011

- Rankki - 1995

- Rankki - 1996

- Richard Mærsk - 2013

- M/T Romø Mærsk - 2015

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2013

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2014

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2014 - Second time

- Stena Barbados - 1999

- Stolt Excellence

- Storön - 1987

- Tina - 1986

- Tärnfjord -1991

- Tärnfjord - 1997

- Tärnfors - 2000

- Tärnhav

- Tärnland - 2000 -1

- Tärnland - 2000 -2

- Tärnland - 2002

- Tärnland - 2001

- Tärnsjö - 2002

- Tärnsund - 1990

- Tärnsund - 2000

- Tärnsund - 2001

- Tärnvik - 2001

- Tärnvik - 2002

- Tärnvind - 1991

- Tärnvind - 2000

- Tärnvind - 2001

- Tärnvind - 2002 -1

- Tärnvind - 2002 -2

- Tärnvind - 2002 -3

- Tärnvåg - 2009

- Ternvik - 2011

- United Polaris - 1995

- Vestria - 1984

- Vestria - 1985 -1

- Vestria - 1985 -2

- Vinga Helena - 2003

- Vingavåg

- Westön

- Links

- Never been on board a ship?

- • Web ship

- Home pages

- • MERSEY SHIPPING - My friend is running a popular blog about scrapped ships

- Thomas diving pictures

- Shipping stuff

- • Maritime pages

- • Light houses

- • Ship Pictures

- Ship Photos

- • Ship Pictures

- Want an exciting job on board?

- • How to obtain German certificates (2005)

- • Looking for job?

- • Careers

- aladdin.st on You Tube

- Aladdin's channel

- • Whale Watching in Sydney

- • A Funky Day in my Office

- • Ek-River in Bad Weather

- • Ek-River - Evacuation of Sick Crew Member by Helicopter

- • Sun rise over the Indian Ocean

- • Tandem operation at Didon Oilfield

- • Rainbow Warrior and the Angry Fishermen

- • How to obtain the gyro compass error

- • How to calibrate and maintan a Riken Keiki GX 2009 gas detector

- • With the Supertanker Argo Pallas in dry dock

- • Fire Fighting Course in Gothenburg - 2004

- • Fire Fighting Course in Gothenburg - 2009

- • Advanced Fire Fighting Course in Malaysia - 2011

- • THAI BOXING - Fight Night in Ratchaburi

- • THAI BOXING - Fight night in Kanchanaburi

- • THAI BOXING - Fight night in Thung Khok, Suphan buri

- • THAI BOXING - Ritttyawannalai School - March 2013

- • Passing a ship in the ice with M/T Astoria - March 2005

- • M/T Dicksi leaving Porvoo in ice - March 2005

- • Pilot boarding M/T Astoria in the ice - March 2005

- Music

- TAXI CD

- Thai

- Contact

The ostrich or Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus) is either of two species of large flightless birds native to Africa, the only living member(s) of the genus Struthio, which is in the ratite family. In 2014, the Somali ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes) was recognized as a distinct species.

The Common Ostrich shares the order Struthioniformes with the kiwis, emus, rheas, and cassowaries. However, phylogenetic studies have shown that it is the sister group to all other members of Palaeognathae and thus the flighted tinamous are the sister group to the extinct moa.

It is distinctive in its appearance, with a long neck and legs, and can run for a long time at the speed of 55 km/h or even up to about 70 km/h (19 m/s; 43 mph), the fastest land speed of any bird. The Common Ostrich is the largest living species of bird and lays the largest eggs of any living bird (extinct elephant birds of Madagascar and the giant moa of New Zealand laid larger eggs).

The Common Ostrich's diet consists mainly of plant matter, though it also eats invertebrates. It lives in nomadic groups of 5 to 50 birds. When threatened, the ostrich will either hide itself by lying flat against the ground, or run away. If cornered, it can attack with a kick of its powerful legs. Mating patterns differ by geographical region, but territorial males fight for a harem of two to seven females.

The Common Ostrich is farmed around the world, particularly for its feathers, which are decorative and are also used as feather dusters. Its skin is used for leather products and its meat is marketed commercially, with its leanness a common marketing point.

Distribution and habitat

Common ostriches formerly occupied Africa north and south of the Sahara, East Africa, Africa south of the rain forest belt, and much of Asia Minor. Today Common Ostriches prefer open land and are native to the savannas and Sahel of Africa, both north and south of the equatorial forest zone.

In Southwest Africa they inhabit the semi-desert or true desert. Farmed Common Ostriches in Australia have established feral populations. The Arabian ostriches in the Near and Middle East were hunted to extinction by the middle of the 20th century. Attempts to reintroduce the Common Ostrich into Israel have failed. Common ostriches have occasionally been seen inhabiting islands on the Dahlak Archipelago, in the Red Sea near Eritrea.

Research conducted by the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany in India found molecular evidence that ostriches lived in India 25,000 years ago. DNA tests on fossilized eggshells recovered from eight archaeological sites in the states of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh found 92% genetic similarity between the eggshells and the North African ostrich. This suggests that ostriches traveled between India and Africa before the two landmasses drifted apart.

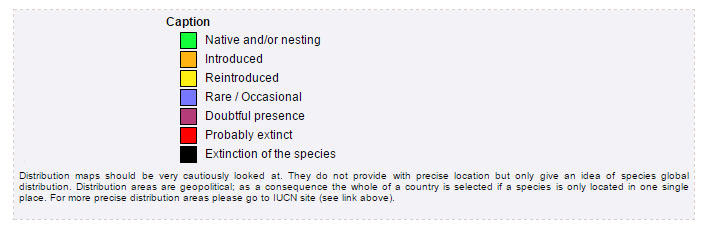

Range map from www.oiseaux.net - Ornithological Portal Oiseaux.net

www.oiseaux.net

is one of those MUST visit pages if you're in to bird watching. You can find just about everything there

Description

Common ostriches usually weigh from 63 to 145 kilograms , or as much as two adult humans. Ostriches of the East African race (S. c. massaicus) averaged 115 kg in males and 100 kg in females, while the nominate subspecies (S. c. camelus) was found to average 111 kg in unsexed adults. Exceptional male ostriches (in the nominate subspecies) can weigh up to 156.8 kg.

At sexual maturity (two to four years), male Common Ostriches can be from 2.1 to 2.8 m in height, while female Common Ostriches range from 1.7 to 2.0 m tall. New chicks are fawn in colour, with dark brown spots.

During the first year of life, chicks grow at about 25 cm per month. At one year of age, Common Ostriches weigh approximately 45 kilograms. Their lifespan is up to 40–45 years.

The feathers of adult males are mostly black, with white primaries and a white tail. However, the tail of one subspecies is buff. Females and young males are greyish-brown and white. The head and neck of both male and female ostriches is nearly bare, with a thin layer of down. The skin of the female's neck and thighs is pinkish gray, while the male's is gray or pink dependent on subspecies.

Ostrich skeleton

By Museum of Veterinary Anatomy FMVZ USP / name of the photographer when stated, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50348028

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50348028

The long neck and legs keep their head up to 2.8 m above the ground, and their eyes are said to be the largest of any land vertebrate: 50 mm in diameter; helping them to see predators at a great distance. The eyes are shaded from sunlight from above. However, the head and bill are relatively small for the birds' huge size, with the bill measuring 12 to 14.3 cm.

Their skin varies in colour depending on the subspecies, with some having light or dark gray skin and others having pinkish or even reddish skin. The strong legs of the Common Ostrich are unfeathered and show bare skin, with the tarsus (the lowest upright part of the leg) being covered in scales: red in the male, black in the female.

The tarsus of the Common Ostrich is the largest of any living bird, measuring 39 to 53 cm in length. The bird has just two toes on each foot (most birds have four), with the nail on the larger, inner toe resembling a hoof. The outer toe has no nail.

The reduced number of toes is an adaptation that appears to aid in running, useful for getting away from predators. Common ostriches can run at a speed over 70 km/h and can cover 3 to 5 m in a single stride.

The wings reach a span of about 2 metres, and the wing chord measurement of 90 cm is around the same size as for the largest flying birds.

The feathers lack the tiny hooks that lock together the smooth external feathers of flying birds, and so are soft and fluffy and serve as insulation. Common ostriches can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. In much of their habitat, temperatures vary as much as 40 °C between night and day.

Claws on the wings

By Frank E. Beddard - The structure and classification of birds (www.archive.org),

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5062936

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5062936

Their temperature control relies in part on behavioural thermoregulation. For example, they use their wings to cover the naked skin of the upper legs and flanks to conserve heat, or leave these areas bare to release heat. The wings also function as stabilizers to give better maneuverability when running.

Tests have shown that the wings are actively involved in rapid braking, turning and zigzag maneuvers. They have 50–60 tail feathers, and their wings have 16 primary, four alular and 20–23 secondary feathers.

The Common Ostrich's sternum is flat, lacking the keel to which wing muscles attach in flying birds. The beak is flat and broad, with a rounded tip. Like all ratites, the ostrich has no crop, and it also lacks a gallbladder.

They have three stomachs, and the caecum is 71 cm long. Unlike all other living birds, the Common Ostrich secretes urine separately from faeces. All other birds store the urine and faeces combined in the coprodeum, but the ostrich stores the faeces in the terminal rectum.

They also have unique pubic bones that are fused to hold their gut. Unlike most birds, the males have a copulatory organ, which is retractable and 20 cm long. Their palate differs from other ratites in that the sphenoid and palatal bones are unconnected.

Listen to the Common ostrich

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Remarks from the Recordist

African Rock Python hissing in foreground

Taxonomy

The Common Ostrich was originally described by Carl Linnaeus from Sweden in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae under its current binomial name.[21] Its scientific name is derived from Latin, struthio meaning "ostrich" and camelus meaning "camel", alluding to its dry habitat.

The Common Ostrich belongs to the ratite order Struthioniformes. Other members include rheas, emus, cassowaries, moa, kiwi and the largest known bird ever, the now-extinct elephant bird (Aepyornis). However, the classification of the ratites as a single order has always been questioned, with the alternative classification restricting the Struthioniformes to the ostrich lineage and elevating the other groups.

Subspecies

Four living subspecies are recognised:

• North African ostrich (S. c. camelus), also called the red-necked ostrich or Barbary ostrich

Lives in North Africa. Historically it was the most widespread subspecies, ranging from Ethiopia and Sudan in the east throughout the Sahel[ to Senegal and Mauritania in the west, and north to Egypt and southern Morocco, respectively.

It has now disappeared from large parts of this range, and it only remains in 6 of the 18 countries where it originally occurred, leading some to consider it Critically Endangered. It is the largest subspecies, at 2.74 m in height and up to 154 kilograms in weight. The neck is pinkish-red, the plumage of males is black and white, and the plumage of females is grey.

• Northern Africa: Algeria, Central African Republic, Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo and Tunisia

• Western Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal

++++++

• South African ostrich (S. c. australis), also commonly known as black-necked ostrich or southern ostrich

Is found south of the rivers Zambezi and Cunene. It is farmed for its meat, leather and feathers in the Little Karoo area of Cape Province.

• Southern Africa: Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe

++++++

• Masai ostrich (S. c. massaicus), also known as the pink-necked ostrich or East African ostrich

It has some small feathers on its head, and its neck and thighs are pink. During the mating season, the male's neck and thighs become brighter. Its range is essentially limited to southern Kenya and eastern Tanzania and Ethiopia and parts of southern Somalia.

• Eastern Africa: Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, Tanzania and Uganda

++++++

• Arabian ostrich (daggerS. c. syriacus), also known as Syrian ostrich or Middle Eastern ostrich

Was formerly very common in the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Iraq; it became extinct around 1966.

• Western Asia: Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen

++++++

An updated version to reflect the correct Southern African

distribution as per Sasol Birds of Southern Africa (2011)

distribution as per Sasol Birds of Southern Africa (2011)

By Struthio_camelus_Distribution_updated.png: en:User:Renato CaniattiAfrica_location_map.svg:

Eric Gaba (Sting - fr:Sting)derivative work: Begoon

This file was derived from:Struthio camelus Distribution updated.png:Africa location map.svg:,

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27811298

Eric Gaba (Sting - fr:Sting)derivative work: Begoon

This file was derived from:Struthio camelus Distribution updated.png:Africa location map.svg:,

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27811298

Somali ostrich

• Somali ostrich (S. molybdophanes) , also known as blue-necked ostrich

Found in southern Ethiopia, northeastern Kenya, and Somalia. The neck and thighs are grey-blue, and during the mating season, the male's neck and thighs become brighter and bluer. The females are more brown than those of other subspecies. It generally lives in pairs or alone, rather than in flocks. Its range overlaps with S. c. massaicus in northeastern Kenya.

• Northeastern Africa: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia

++++++

Some analyses indicate that the Somali ostrich may be better considered a full species, but there is no consensus among experts about this. The Tree of Life Project, The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World and IOC recognize it as a different species, but Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World does not.

BirdLife International has reviewed the proposed split and accepted it. Mitochondrial DNA haplotype comparisons suggest that it diverged from the other ostriches not quite 4 mya due to formation of the East African Rift.

Hybridization with the subspecies that evolved southwestwards of its range, S. c. massaicus, has apparently been prevented from occurring on a significant scale by ecological separation, the Somali ostrich preferring bushland where it browses middle-height vegetation for food while the Masai ostrich is, like the other subspecies, a grazing bird of the open savanna and miombo habitat.

The population from Río de Oro was once separated as Struthio camelus spatzi because its eggshell pores were shaped like a teardrop and not round. However, as there is considerable variation of this character and there were no other differences between these birds and adjacent populations of S. c. camelus, the separation is no longer considered valid.

This population disappeared in the latter half of the 20th century. There were 19th-century reports of the existence of small ostriches in North Africa; these are referred to as Levaillant's ostrich (Struthio bidactylus) but remain a hypothetical form not supported by material evidence.

Behaviour and ecology

Common ostriches normally spend the winter months in pairs or alone. Only 16 percent of Common Ostrich sightings were of more than two birds. During breeding season and sometimes during extreme rainless periods ostriches live in nomadic groups of five to 100 birds (led by a top hen) that often travel together with other grazing animals, such as zebras or antelopes. Ostriches are diurnal, but may be active on moonlit nights. They are most active early and late in the day. The male Common Ostrich territory is between 2 and 20 km2.

With their acute eyesight and hearing, Common Ostriches can sense predators such as lions from far away. When being pursued by a predator, they have been known to reach speeds in excess of 70 km/h, and can maintain a steady speed of 50 km/h, which makes the Common Ostrich the world's fastest two-legged animal.

When lying down and hiding from predators, the birds lay their heads and necks flat on the ground, making them appear like a mound of earth from a distance, aided by the heat haze in their hot, dry habitat.

When threatened, Common Ostriches run away, but they can cause serious injury and death with kicks from their powerful legs. Their legs can only kick forward.

“Head in the sand” myth

Contrary to popular belief, ostriches do not bury their heads in sand to avoid danger. This myth likely began with Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79), who wrote that ostriches “imagine, when they have thrust their head and neck into a bush, that the whole of their body is concealed”

This may have been a misunderstanding of their sticking their heads in the sand to swallow sand and pebbles to help digest their fibrous food,[57] or, as National Geographic suggests, of the defensive behavior of lying low, so that they may appear from a distance to have their head buried.

Another possible origin for the myth lies with the fact that ostriches keep their eggs in holes in the sand instead of nests, and must rotate them using their beaks during incubation; digging the hole, placing the eggs, and rotating them might each be mistaken for an attempt to bury their heads in the sand.

Feeding

They mainly feed on seeds, shrubs, grass, fruit and flowers; occasionally they also eat insects such as locusts. Lacking teeth, they swallow pebbles that act as gastroliths to grind food in the gizzard. When eating, they will fill their gullet with food, which is in turn passed down their esophagus in the form of a ball called a bolus.

The bolus may be as much as 210 ml. After passing through the neck (there is no crop) the food enters the gizzard and is worked on by the aforementioned pebbles. The gizzard can hold as much as 1,300 g, of which up to 45% may be sand and pebbles.

Common ostriches can go without drinking for several days, using metabolic water and moisture in ingested plants, but they enjoy liquid water and frequently take baths where it is available.[44] They can survive losing up to 25% of their body weight through dehydration.

Mating

Common ostriches become sexually mature when they are 2 to 4 years old; females mature about six months earlier than males. As with other birds, an individual may reproduce several times over its lifetime. The mating season begins in March or April and ends sometime before september.

The mating process differs in different geographical regions. Territorial males typically boom in defence of their territory and harem of two to seven hens; the successful male may then mate with several females in the area, but will only form a pair bond with a 'major' female.

The cock performs with his wings, alternating wing beats, until he attracts a mate. They will go to the mating area and he will maintain privacy by driving away all intruders. They graze until their behaviour is synchronized, then the feeding becomes secondary and the process takes on a ritualistic appearance.

The cock will then excitedly flap alternate wings again, and start poking on the ground with his bill. He will then violently flap his wings to symbolically clear out a nest in the soil. Then, while the hen runs a circle around him with lowered wings, he will wind his head in a spiral motion. She will drop to the ground and he will mount for copulation.

Common ostriches raised entirely by humans may direct their courtship behaviour not at other ostriches, but toward their human keepers.

The female Common Ostrich lays her fertilised eggs in a single communal nest, a simple pit, 30 to 60 cm deep and 3 m wide, scraped in the ground by the male. The dominant female lays her eggs first, and when it is time to cover them for incubation she discards extra eggs from the weaker females, leaving about 20 in most cases.

A female Common Ostrich can distinguish her own eggs from the others in a communal nest. Ostrich eggs are the largest of all eggs, though they are actually the smallest eggs relative to the size of the adult bird — on average they are 15 cm long, 13 cm wide, and weigh 1.4 kilograms, over 20 times the weight of a chicken's egg and only 1 to 4% the size of the female. They are glossy cream-coloured, with thick shells marked by small pits.

Egg

By Klaus Rassinger und Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36975629

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36975629

The eggs are incubated by the females by day and by the males by night. This uses the colouration of the two sexes to escape detection of the nest, as the drab female blends in with the sand, while the black male is nearly undetectable in the night.

The incubation period is 35 to 45 days, which is rather short compared to other ratites. This is believed to be the case due to the high rate of predation. Typically, the male defends the hatchlings and teaches them to feed, although males and females cooperate in rearing chicks.

Fewer than 10% of nests survive the 9 week period of laying and incubation, and of the surviving chicks, only 15% of those survive to 1 year of age. However, among those Common Ostriches who survive to adulthood, the species is one of the longest-living bird species. Common ostriches in captivity have lived to 62 years and 7 months.

Fried egg

By メルビル - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42959721

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42959721

Predators

As a flightless species in the rich biozone of the African savanna, the Common Ostrich must face a variety of formidable predators throughout its life cycle. Animals that prey on ostriches of all ages may include cheetahs, lions, leopards, African hunting dogs, and spotted hyenas.

Common ostriches can often outrun most of their predators in a pursuit, so most predators will try to ambush an unsuspecting bird using obstructing vegetation or other objects. A notable exception is the cheetah, which is the most prolific predator of adult Common Ostriches due to its own great running speeds.

Predators of nests and young Common Ostriches include jackals, various birds of prey, warthogs, mongoose and Egyptian Vultures. If the nest or young are threatened, either or both of the parents may create a distraction, feigning injury.

However, they may sometimes fiercely fight predators, especially when chicks are being defended, and have been capable of killing even lions in such confrontations.

Status and conservation

The wild Common Ostrich population has declined drastically in the last 200 years, with most surviving birds in reserves or on farms. However, its range remains very large (9,800,000 square kilometres), leading the IUCN and BirdLife International to treat it as a species of Least Concern.

Of its 5 subspecies, the Arabian ostrich (S. c. syriacus) became extinct around 1966, and the North African ostrich (S. c. camelus) has declined to the point where it now is included on CITES Appendix I and some treat it as Critically Endangered.

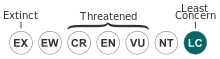

Conservation status

Least Concern

(IUCN 3.1)

IUCN Red List

of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T45020636A95139620.

doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T45020636A95139620.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T45020636A95139620.en. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Ostriches and humans

Common ostriches have inspired cultures and civilizations for 5,000 years in Mesopotamia and Egypt. A statue of Arsinoe II of Egypt riding a Common Ostrich was found in a tomb in Egypt.[99] Hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari use ostrich eggshells as water containers, punching a hole in them.

They also produce jewelry from it. The presence of such eggshells with engraved hatched symbols dating from the Howiesons Poort period of the Middle Stone Age at Diepkloof Rock Shelter in South Africa suggests Common Ostriches were an important part of human life as early as 60,000 BP.

Scene with Common Ostriches, Roman mosaic, 2nd century AD

By Unknown - this site, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3479052

Hunting and farming

In Roman times, there was a demand for Common Ostriches to use in venatio games or cooking. They have been hunted and farmed for their feathers, which at various times have been popular for ornamentation in fashionable clothing (such as hats during the 19th century).

Their skins are valued for their leather. In the 18th century they were almost hunted to extinction; farming for feathers began in the 19th century. At the start of the 20th century there were over 700,000 birds in captivity.

The market for feathers collapsed after World War I, but commercial farming for feathers and later for skins and meat became widespread during the 1970s. Common ostriches are so adaptable that they can be farmed in climates ranging from South Africa to Alaska.

Fashion accessories made from Common Ostrich feathers, Amsterdam, 1919

By Cornelis Johan Hofker (1886-1936) [2] - [1],

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31529045

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31529045

In Eastern Christianity it is common to hang decorated Common Ostrich eggs on the chains holding the oil lamps. The initial reason was probably to prevent mice and rats from climbing down the chain to eat the oil.

Another, symbolical explanation is based in the fictitious tradition that female Common Ostriches do not sit on their eggs, but stare at them incessantly until they hatch out, because if they stop staring even for a second the egg will addle. This is equated to the obligation of the Christian to direct his entire attention towards God during prayer, lest the prayer be fruitless.

Common ostriches have been farmed in South Africa since the beginning of the 19th century. According to Frank G. Carpenter, the English are credited with first taming Common Ostriches outside Cape Town. Farmers captured baby Common Ostriches and raised them successfully on their property, and were able to obtain a crop of feathers every seven to eight months instead of killing wild Common Ostriches for their feathers.

It is claimed that Common Ostriches produce the strongest commercial leather. Common ostrich meat tastes similar to lean beef and is low in fat and cholesterol, as well as high in calcium, protein and iron. Uncooked, it is dark red or cherry red, a little darker than beef. Ostrich stew is a dish prepared using Common Ostrich meat.

Some Common Ostrich farms also cater to agri-tourism, which may produce a substantial portion of the farm's income. This may include tours of the farmlands, souvenirs, or even ostrich rides.

Various ostrich leather profucts.

The ostrich leather is used for material of bag and belt, purse.

The ostrich leather is used for material of bag and belt, purse.

By Irostrich - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38799097

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38799097

Attacks

Common ostriches typically avoid humans in the wild, since they correctly assess humans as potential predators. If approached, they often run away, but sometimes ostriches can be very aggressive when threatened, especially if cornered, and may also attack if they feel the need to defend their territories or offspring.

Similar behaviors are noted in captive or domesticated Common Ostriches, which retain the same natural instincts and can occasionally respond aggressively to stress. When attacking a person, Common Ostriches deliver slashing kicks with their powerful feet, armed with long claws, with which they can disembowel or kill a person with a single blow.

In one study of Common Ostrich attacks, it was estimated that two to three attacks that result in serious injury or death occur each year in the area of Oudtshoorn, South Africa, where a large number of Common Ostrich farms are set next to both feral and wild Common Ostrich populations.

Jacksonville, Florida, man with a Common Ostrich-drawn cart, circa 1911

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18870

Racing

In some countries, people race each other on the backs of Common Ostriches. The practice is common in Africa and is relatively unusual elsewhere. The Common Ostriches are ridden in the same way as horses with special saddles, reins, and bits. However, they are harder to manage than horses.

The racing is also a part of modern South African culture. Within the United States, a tourist attraction in Jacksonville, Florida, called 'The Ostrich Farm' opened up in 1892; it and its races became one of the most famous early attractions in the history of Florida.

Likewise, the arts scene in Indio, California, consists of both ostrich and camel racing. Chandler, Arizona, hosts the annual "Ostrich Festival", which features Common Ostrich races. Racing has also occurred at many other locations such as Virginia City in Nevada, Canterbury Park in Minnesota, Prairie Meadows in Iowa, Ellis Park in Kentucky, and the Fairgrounds in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Common ostrich race in 1933 in The Netherlands

This media file is from the Open Images project, an initiative from the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision and Kennisland

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sighted: (Date of first photo that I could use) 15th of November 2014

Location: Ghoha Hills, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 20 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 20 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 20 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich family - 21 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 21 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 21 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

Common Ostrich - 22 November 2014 - Kalahari Desert, Botswana

PLEASE! If I have made any mistakes identifying any bird, PLEASE let me know on my guestbook

You are visitor no.

To www.aladdin.st since December 2005