- Year: 1984-1989

- 1984

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vestria

- 1985

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Corona

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vestria

- • Christmas on board M/T Vestria

- 1986

- • Aladdin is back to School after the Christmas holiday

- • Aladdin's adventure at Vinterspelen i Härnösand

- • Aladdin's adventure at Navigation School in Göteborg

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordic Link

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Tina

- • Aladdin's adventure in Helsingborg - November 1986

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Bellatrix

- 1987

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Ewaria

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Katarina

- • Aladdin's adventure at Roskilde Festivalen 1987

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Storön

- • Aladdin's adventure in Båstad and Mölle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nova

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Bleking

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Aurum

- 1988

- • Aladdin's adventure in West Berlin

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Lindfjord

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordanhav

- • Aladdin's adventure in SE Asia

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Autumn 1988

- • Christmas on board Nils Dacke

- 1989

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nils Dacke

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Nordic Stream

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Spring 1989

- • Aladdin taking down the Berlin Wall

- • Aladdin's adventure in Berlin - New Year 1989

- Year: 1990-1999

- 1990

- • Aladdin in Navigation school - Spring 1990

- • Aladdin's adventure in Paris

- • Aladdin's adventure in New York

- • Aladdin's adventure in Amsterdam - Queen's day

- • Aladdin's adventure on board S/S Ingo

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bellona

- • Aladdin's adventure at The Wall concert in Berlin July 1990

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Westön

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsund

- 1991

- • Aladdin's adventure in Florida

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfjord

- • Aladdin's adventure in Amsterdam - Queen's day

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Eken

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Vingavåg

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord Nils Dacke

- 1992

- • Aladdin's adventure in Asia - India, Thailand and Japan

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Breant

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Artic 1

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bituma

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & India 1992 to 93

- 1993

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & Australia

- • Aladdin's adventure in a Norwegian jail

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Forsvik

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bituma

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok 1993

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok & India 1992 to 93

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- 1994

- • Aladdin's Adventure in Thailand

- • Aladdin's trekking adventure in Nepal

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnhav

- 1995

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T United Polaris

- • Aladdin is moving to Bangkok

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margita

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Rankki

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Margaron

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Kaprifol

- 1996

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T Rankki

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - March 1996

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Argo Athena

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Summer/ Autumn 1996

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Argo Pallas

- 1997

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Songkran 1997

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ekturus

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Sun

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfjord

- • Aladdin in Stockholm/ His first internet experience

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Stolt Excellence

- 1998

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - Winter 1998

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Asian Progress

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok and Mölle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Stena Barbados

- 1999

- • Aladdin's adventure in the Caribbean

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Alstern

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- Year: 2000-2009

- 2000

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnfors

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsund

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Halmia

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- 2001

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Master Cody

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Nelly

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnsund

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on bord M/T Tärnvik

- 2002

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnland

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvik

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnsjö

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvind

- • Aladdin buys his first digital camera

- • Christmas Horror Story

- • Aladdin's Christmas adventure in Go:teborg

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Fure Sun

- 2003

- • Aladdin's disappointment coming home to FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Vinga Helena

- • Aladdin's adventure in Chiang Mai

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Anton

- 2004

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T CT Sky

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Prospero

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cape Town, South Africa

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Jupiter

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Framnäs

- • Aladdin's FIRE FIGHTING course in Göteborg

- • Aladdin moving in to his not yet ready condo

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Astoria

- 2005

- • Aladdin in Germany - How to obtain German licences

- • Aladdin's Adventure on board M/T Astoria

- • Aladdin celebrating the summer 2005

- • Aladdin in Hamburg taking a course in German Shipping Legislation

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Pegasus

- 2006

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cairo, Egypt - April 2006

- • Aladdin at the DANGEROUS GOODS (IMDG) course

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Rainbow Warrior

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Jupiter

- • Aladdin's adventure in Rome and Thailand

- 2007

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Barcarolle

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Marimba

- • Aladdin's first sick leave

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Barcarolle

- 2008

- • Aladdin's adventure in Los Angeles & Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Provider

- • Aladdin's holiday -Autumn 2008

- • Aladdin training at NTC in Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Bro Promotion

- 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in Thailand - Malaysia - Gothenburg

- • Aladdin's FIRE FIGHTING course in Göteborg

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Tärnvåg

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - Summer 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in Seoul and Tepei

- • Aladdin is back FUNKY TOWN again - 2009

- • Aladdin on tour with Bangkok By Bike - October 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - October 2009

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-River

- Year: 2010-2015

- 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Funky Town - March/ April 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure during Songkran in Bangkok - 2010

- • Aladdin's training at NTC in Manila

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - April/ May 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Little Isan in Bangkok - May 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure during the Red Shirt protests - 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-Star

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-River

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ek-Star

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - October 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Manila - November 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - November 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - December 2010

- • Aladdin's adventure in Phnom Penh - VISA RUN

- 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN - January 2011

- • Aladdin's diving adventure in Pattaya - January 2011

- • Aladdin's Chinese New Year adventure in Bangkok

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok - February 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- March 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in Vientiane, Laos - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Ternvik

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- July 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club- August 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cambodia - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure on board DE/T Randgrid

- • Aladdin's adventure at Bangkok Fight Club - September 2011

- • Aladdin's Advanced Fire Fighting course in Johor Bahru

- • Aladdin's Proficiency in Survival Craft & Rescue Boat course in Singapore

- • Aladdin's Advanced in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2011

- • Aladdin's escape to Pattaya during the flooding of Bangkok

- • Aladdin returns to a flooded Bangkok

- • Aladdin adventure in a flooded Bangkok - November 2011

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2011

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Maersk Cassandra

- 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Singapore - March 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - March 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure during Songkran in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Tokyo - VISA RUN

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN again - April 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure at Rajadamnern Muay Thai Stadium - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure with Bangkok Photographers - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure at Thai Navy's shooting range - May 2012

- • Aladdin adventure in Shanghai - VISA run - May 2012

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN again - June 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure with Bangkok Photographers at Benchasiri Park in BANGKOK

- • Hangover Man's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - June 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Maersk Claudia

- • Aladdin's adventure in Hong Kong

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - September 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2012

- • Aladdin's acupuncture adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - October 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure @ My Thai Language School in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin adventure in Siem Reap - VISA run - October 2012

- • Aladdin is back in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin's adventure at Faulty Towers: The Dining Experience in FUNKY TOWN/ BANGKOK

- • Fight night in Lao Khwan, Kanchanaburi, Thailand

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Mumbai/ Bombay - Advanced Medical Training - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Chennai/ Madras - DML & Para 16 Course - November 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure onboard Jet Airways flight to Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN

- • Aladdin is back home in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2012

- • Fight night in Thung Khok, Suphan Buri - December 2012

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - December 2012

- • Aladdin's last weekend in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN 2012?

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Britta Mærsk

- 2013

- • Aladdin is back in FUNKY TOWN - March 2013

- • American girl in yet another Muay Thai fight - March 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok/ FUNKY TOWN - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Singapore - Visa Run - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in Bangkok during Songkran - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure at Thai Navy's shooting range in Bangkok

- • Fight night at Rangsit International Boxing Stadium - April 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN/ Bangkok - May 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Richard Mærsk

- • Aladdin's adventure in Istanbul - August 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure in FUNKY TOWN/ Bangkok - August 2013

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Birthday party in Thailand

- • Potluck in Bangkok

- • New Year in Singapore

- 2014

- • Aladdin buy new boxing gloves with the American girl - January 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Honolulu - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Asoke/ Sukhumvit intersection protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Ratchaprasong protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Silom/ Lumpini intersection protest site - January 2014

- • SHUT DOWN Bangkok - Victory Monument intersection protest site - January 2014

- • Bridge Team Management course at Norwegian Training Center in Manila - January 2014

- • FRAMO course for Officers at Norwegian Training Center in Manila - February 2014

- • Going to Monk Ordination in Ban Chang, Rayong - February 2014

- • Monk Ordination in Thailand - February 2014

- • At Bangkok Wing Chun in Bang Na - February 2014

- • Last Night in Bangkok - March 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Voting for the EU Parliament - May 2014

- • Advanced Fire Fighting Course in Helsingborg - May 2014

- Skånsk Gästgiveri Tour - May 2014

- • Fire Fighting Course in Kalmar - May 2014

- • Falukorv - Thai Style - May 2014

- • Monk Ordination in Bang Pa In - June 2014

- Falukorv - Skåne Staajl - June 2014

- • Aladdin'n goes to the hospital - June 2014

- • Urban Safari “Hidden Gem” with Bangkok Photographers - June 2014

- • Visa run to Las Vegas - June 2014

- • Arriving to Las Vegas - June 2014

- • Hoover Dam - June 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure at Hangover Heaven - June 2014

- • Grand Canyon - June 2014

- • Aladdin's STOP OVER in Tokyo - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Cha-am - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Tanzania - July 2014

- • Aladdin's African Safari adventure - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure in Zanzibar - July 2014

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Roy Mærsk

- • Aladdin's adventure in Skåne - October 2014

- • Aladdin going back home to Bangkok - October 2014

- • Halloween in Bangkok - October 2014

- • Aladdin's safari adventure in Africa - November 2014

- • The King's Birth Day/ Father's Day at Ratchadamnoen Road - 5th of December 2014

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #33 - Talat Rot Fai

- • December in Bangkok

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #34 - Tha Chalom

- • VISA run again - Aladdin's adventure on the Mekong River in Laos

- 2015

- • Aladdin flying back to Bangkok from Laos - January 2015

- • Aladdin's adventure on board Maersk Mediterranean at the TPP Terminal on Koh Sichang

- • Aladdin's safari adventure at Khao Yai National Park

- • Aladdin's Saturday night adventure in the Benjasiri Park in Bangkok

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #1 - Erawan Museum - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #2 - Coocking Thai Food - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #2 - Coocking Thai Food - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #3 - Royal Air Force Museum - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #4 - Rice Barge Cruise on Chao Phraya River - January '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #5 - Ayutthaya Cruise Tour - February '15

- • Thai Funeral at Wat Hua Lamphong (วัดหัวลำโพง) - February '15

- • Birthday party in Bangkok - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #6 - Siam Naramit Show - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #7 - At Camillian Hospital - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #8 - Museum of Siam - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #9 - Bangkok National Museum - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #10 - The National Museum of Royal Barges - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #11 - Ancient City - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #12 - Rock Around Asia Art Gallery - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #13 - Thai Labour Museum - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #14 - Chinese New Year in Bangkok China Town - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #15 - Asiatique The Riverfront - February '15

- • Bangkok Photographers - Photo Walk #36 - Wat Salak Tai Community

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #16 - Chao Phraya Express Boat - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #17 - Koh Kret - February '15

- • What to do for fun when you're too old for party? - How to kill a day in Bangkok #18 - Temple tour with Chao Phraya Tourist Boat - March '15

- • Visa run to Poi Pet, Cambodia - March '15

- • Aladdin's adventure on board M/T Romø Mærsk

- Search ship by name

- Alstern - 1999

- Argo Athena

- Argo Pallas

- Artic 1

- Asian Progress

- Astoria - 2004

- Astoria - 2005

- Aurum - 1987

- Brcarolle - 2007-1

- Barcarolle - 2007-2

- Bellatrix - 1986

- Bellona

- Bituma - 1992

- Bituma - 1993

- Bleking - 1987

- Breant

- Britta Mærsk - 2012

- Bro Anton - 2003

- Bro Jupiter - 2004

- Bro Jupiter - 2006

- Bro Nelly

- Bro Promotion - 2008

- Bro Provider - 2008

- Corona - 1985

- CT Sky - 2004

- CT Star - 2003

- CT Star - 2003

- CT Sun

- Eken

- Ek-River - 2009

- Ek-River - 2010

- M/T Ek-Star - 1210 -1

- Ek-Star - 2010 -2

- Ekturus

- Ewaria - 1987

- Forsvik

- Framnäs - 2003 -1

- Framnäs - 2003-2

- Framnäs - 2004

- Fure Sun - 2002

- Halmia - 2000

- Kaprifol

- Katarina - 1987

- Lindfjord - 1988

- Maersk Cassandra - 2011

- Maersk Claudia - 2012

- Margaron - 1993

- Margaron - 1994

- Margaron - 1995

- Margita

- Marimba - 2007

- Master Cody - 2001

- Nils Dacke - 1988

- Nils Dacke - 1989

- Nils Dacke - 1991

- Nordanhav - 1988

- Nordic Link - 1986

- Nordic Stream - 1991

- Nova - 1987

- Pegasus - 2005

- Prospero - 2004

- Rainbow Warrior - 2006

- Randgrid - 2011

- Rankki - 1995

- Rankki - 1996

- Richard Mærsk - 2013

- M/T Romø Mærsk - 2015

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2013

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2014

- M/T Roy Mærsk - 2014 - Second time

- Stena Barbados - 1999

- Stolt Excellence

- Storön - 1987

- Tina - 1986

- Tärnfjord -1991

- Tärnfjord - 1997

- Tärnfors - 2000

- Tärnhav

- Tärnland - 2000 -1

- Tärnland - 2000 -2

- Tärnland - 2002

- Tärnland - 2001

- Tärnsjö - 2002

- Tärnsund - 1990

- Tärnsund - 2000

- Tärnsund - 2001

- Tärnvik - 2001

- Tärnvik - 2002

- Tärnvind - 1991

- Tärnvind - 2000

- Tärnvind - 2001

- Tärnvind - 2002 -1

- Tärnvind - 2002 -2

- Tärnvind - 2002 -3

- Tärnvåg - 2009

- Ternvik - 2011

- United Polaris - 1995

- Vestria - 1984

- Vestria - 1985 -1

- Vestria - 1985 -2

- Vinga Helena - 2003

- Vingavåg

- Westön

- Links

- Never been on board a ship?

- • Web ship

- Home pages

- • MERSEY SHIPPING - My friend is running a popular blog about scrapped ships

- Thomas diving pictures

- Shipping stuff

- • Maritime pages

- • Light houses

- • Ship Pictures

- Ship Photos

- • Ship Pictures

- Want an exciting job on board?

- • How to obtain German certificates (2005)

- • Looking for job?

- • Careers

- aladdin.st on You Tube

- Aladdin's channel

- • Whale Watching in Sydney

- • A Funky Day in my Office

- • Ek-River in Bad Weather

- • Ek-River - Evacuation of Sick Crew Member by Helicopter

- • Sun rise over the Indian Ocean

- • Tandem operation at Didon Oilfield

- • Rainbow Warrior and the Angry Fishermen

- • How to obtain the gyro compass error

- • How to calibrate and maintan a Riken Keiki GX 2009 gas detector

- • With the Supertanker Argo Pallas in dry dock

- • Fire Fighting Course in Gothenburg - 2004

- • Fire Fighting Course in Gothenburg - 2009

- • Advanced Fire Fighting Course in Malaysia - 2011

- • THAI BOXING - Fight Night in Ratchaburi

- • THAI BOXING - Fight night in Kanchanaburi

- • THAI BOXING - Fight night in Thung Khok, Suphan buri

- • THAI BOXING - Ritttyawannalai School - March 2013

- • Passing a ship in the ice with M/T Astoria - March 2005

- • M/T Dicksi leaving Porvoo in ice - March 2005

- • Pilot boarding M/T Astoria in the ice - March 2005

- Music

- TAXI CD

- Thai

- Contact

Bryde's whale

Bryde's whale or the Bryde's whale complex (/bruːdə/brew-də) putatively comprises two species of rorqual and maybe three. The "complex" means the number and classification remains unclear because of a lack of definitive information and research. The common Bryde's whale (Balaenoptera brydei, Olsen, 1913) is a larger form that occurs worldwide in warm temperate and tropical waters, and the Sittang or Eden's whale (B. edeni, Anderson, 1879) is a smaller form that may be restricted to the Indo-Pacific.

Also, a smaller, coastal form of B. brydei is found off southern Africa, and perhaps another form in the Indo-Pacific differs in skull morphology, tentatively referred to as the Indo-Pacific Bryde's whale. The recently described Omura's whale (B. omurai, Wada et al. 2003), was formerly considered a "pygmy" form of Bryde's, but is now recognized as a distinct species.

B. brydei gets its specific and common name from Johan Bryde, Norwegian consul to South Africa who helped establish the first modern whaling station in the country, while B. edeni gets its specific and common name from Sir Ashley Eden, former High Commissioner of Burma (Myanmar). Sittang whale refers to the type locality of the species. In Thailand, locals distinguished Sittang whales different from B.edeni, and it is unclear whether Sittang whales were applied for later classified Omura's whales by locals.

Members of the Bryde's whale complex are moderately sized rorquals, falling behind sei whales, but being larger than Omura's whale and the relatively small minke whales. The largest measured by Olsen (1913) was a 14.95 m female caught off Durban in November 1912, while the longest of each sex measured by Best (1977) at the Donkergat whaling station in Saldanha Bay, South Africa, were a 15.51 m female caught in October 1962 and a 14.56 m male caught in April 1963; both were the offshore form.

At physical maturity, the coastal form off South Africa averages 13.1 m for males and 13.7 m for females, while the South Africa offshore form averages 13.7 and 14.4 m. The coastal form near Japan is slightly smaller, with adult males averaging 12.9 m and adult females 13.3 m.

At sexual maturity, males average 11.9 m and females 12 m near Japan. Sexual maturity is reached at 8–11 years for both sexes in the offshore form off South Africa. At birth, they are 3.95–4.15 m. The body mass of Bryde's whales can range 12–25 metric tons.

Bryde's whale range

Bryde's whale is a baleen whale, more specifically a rorqual belonging to the same group as blue whales and humpback whales. It has twin blowholes with a low splashguard to the front. Like other rorquals, it has no teeth, but has two rows of baleen plates.

Bryde's whales closely resemble their close relative the sei whale. They are remarkably elongated (even more so than fin whales), with the greatest height of the body being one-seventh their total length – compared to 1/6.5 to 1/6.75 in fin whales and only 1/5.5 in sei whales. Bryde's are dark smoky grey dorsally and usually white ventrally, whereas sei whales are often a galvanized blue-grey dorsally and have a variably sized white patch on the throat, a posteriorly oriented white anchor-shaped marking between the pectoral fins, and are blue-grey beyond the anus – although Bryde's off South Africa can have a similar irregular white patch on the throat.

Bryde's have a straight rostrum with three longitudinal ridges that extend from the blowholes, where the auxiliary ridges begin as depressions, to the tip of the rostrum. The sei whale, like other rorquals, has a single median ridge, as well as a slightly arched rostrum, which is accentuated at the tip. Bryde's usually have dark grey lower jaws, whereas sei whales are lighter grey. Bryde's have 250–370 pairs of short, slate grey baleen plates with long, coarse, lighter grey or white bristles that are 40 cm long by 20 cm wide, while sei whales have longer, black or dark grey baleen plates with short, curling, wool-like bristles.

The 40 to 70 ventral pleats extend to or past the umbilicus, occupying about 58% and 57% of the total length, respectively; sei whales, though, have ventral pleats that extend only halfway between the pectoral fins and umbilicus, occupying only 45-47% of the total body length, whereas their umbilicus is usually 52% of the total body length. Both species are often covered with white or pink oval scars caused by bites from cookie-cutter sharks.

Bryde's whales have an upright, falcate dorsal fin that is up to 46.25 cm in height, averages 34.4 cm, and is usually between 30 and 37.5 cm. It is often frayed or ragged along its rear margin and located about two-thirds of the way along the back. The broad, centrally notched tail flukes rarely break the surface. The flippers are small and slender.

Their blow is columnar or bushy, about 3.0–4.0 m high. Sometimes, they blow or exhale while under water. Bryde's whales display seemingly erratic behaviour compared to other baleens, because they surface at irregular intervals and can change directions for unknown reasons.

They usually appear individually or in pairs, and occasionally in loose aggregations up to 20 animals around feeding areas. They are more active on water surface than sei whales, and this tendency becomes even stronger in coastal form.

They regularly dive for about 5–15 minutes (maximum of 20 minutes) after four to seven blows. Bryde's whales are capable of reaching depths down to 300 m. When submerging, these whales do not display their flukes. Bryde's whales commonly swim at 1.6–6.4 km/h, but can reach 19–24 km/h. They sometimes generate short (0.4 seconds) powerful, low frequency vocalizations that resemble a human moan.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Humpback whale

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1) - IUCN Red List

of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 January 2013

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 January 2013

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a species of baleen whale. One of the larger rorqual species, adults range in length from 12–16 m and weigh about 36,000 kg. The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is known for breaching and other distinctive surface behaviors, making it popular with whale watchers. Males produce a complex song lasting 10 to 20 minutes, which they repeat for hours at a time. Its purpose is not clear, though it may have a role in mating.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 25,000 km each year. Humpbacks feed only in summer, in polar waters, and migrate to tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth in the winter when they fast and live off their fat reserves. Their diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net technique.

Like other large whales, the humpback was a target for the whaling industry. Once hunted to the brink of extinction, its population fell by an estimated 90% before a 1966 moratorium. While stocks have partially recovered, entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships and noise pollution continue to impact the population of 80,000.

Both male and female humpback whales vocalize, but only males produce the long, loud, complex "song" for which the species is famous. Each song consists of several sounds in a low register, varying in amplitude and frequency and typically lasting from 10 to 20 minutes. Individuals may sing continuously for more than 24 hours. Cetaceans have no vocal cords. They vocalize by forcing air through their massive nasal cavities (blowholes).

Whales within a large area sing a single song. All North Atlantic humpbacks sing the same song, while those of the North Pacific sing a different song. Each population's song changes slowly over a period of years without repeating.

Scientists are unsure of the purpose of whale songs. Only males sing, suggesting one purpose is to attract females. However, many of the whales observed to approach a singer are other males, often resulting in conflict. Singing may, therefore, be a challenge to other males. Some scientists have hypothesized the song may serve an echolocative function. During the feeding season, humpbacks make unrelated vocalizations for herding fish into their bubble nets.

Humpback whales make other sounds to communicate, such as grunts, groans, "thwops", snorts and barks.

Listen to the Humpback whale

Humpbacks inhabit all major oceans, in a wide band running from the Antarctic ice edge to 77° N latitude. The four global populations are North Pacific, Atlantic, Southern Ocean and Indian Ocean populations. These populations are distinct. Although the species has cosmopolitan distribution and is usually not considered to cross the equator line, seasonal observations at Cape Verde suggest possible interactions among populations from both hemisphere.

Whales were once uncommon in the eastern Mediterranean or the Baltic Sea, but have increased their presence in both waters as global populations have recovered. Recent increases within the Mediterranean basin, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may migrate into the inland sea in the future. They have also returned to Skagerrak and Kattegat, as well as Scandinavian fjords such as the Kvænangen, where they had not been observed for decades.

In the North Atlantic, feeding areas range from Scandinavia to New England. Breeding occurs in the Caribbean and Cape Verde. In the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, whales may breed off Brazil, as well the coasts of central, southern and southeastern Africa (including Madagascar). Whale visits into Gulf of Mexico have been infrequent, but occurred in the gulf historically. In the South Atlantic, about 10% of world population of the species possibly migrate to Gulf of Guinea. Comparison of songs between those at Cape Lopez and Abrolhos Archipelago indicate that trans-Atlantic mixings between western and southeastern populations occur.

A large population spreads across the Hawaiian Islands every winter, ranging from the island of Hawaii in the south to Kure Atoll in the north. These animals feed in areas ranging from the coast of California to the Bering Sea. Humpbacks were first observed in Hawaiian waters in the mid-19th century and might have gained a dominance over North Pacific right whales as the right whales were hunted to near-extinction.

A 2007 study identified seven individuals then wintering off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica as having traveled from the Antarctic—around 8,300 km. Identified by their unique tail patterns, these animals made the longest documented mammalian migration. In Australia, two main migratory populations were identified, off the west and east coasts. These two populations are distinct, with only a few females in each generation crossing between the two groups.

In Panama and Costa Rica, humpback whales come from both the Southern Hemisphere (July–October with over 2,000 whales) and the Northern Hemisphere (December–March numbering about 300.) South Pacific populations migrating off mainland New Zealand, Kermadec Islands, and Tasmania are increasing, but less rapidly than in Australian waters because of illegal whaling by the Soviet Union in the 1970s.

Some recolonizing habitats are confirmed, especially in the North and South Atlantic (e.g. English and Irish coasts, English Channel to coasts in the north such as the North Sea and Wadden Sea, South Pacific (e.g. New Zealand coasts and Niue), pelagic islands of Chile such as Isla Salas y Gómez and the Easter Island where possibilities of undocumented wintering grounds have been considered, southern fiords of Chile and Peru (e.g. Gulf of Penas, Strait of Magellan, Beagle Channel) and in Asia.

Areas in the Philippines such as in Babuyan Islands, Cagayan and Calayan and Pasaleng Bay, Ryukyu Islands the Volcano Islands in Japan and the Northern Mariana Islands recently, again became stable/growing wintering grounds while Marshall Islands, Vietnamese, Taiwanese and Chinese coasts show slow or no obvious recovery.

Whales again migrate off Japanese archipelagos and into the Sea of Japan. Connections between these stocks and whales seen in Sea of Okhotsk, on Kamchatka coasts and around Commander Islands have been studied.[69] Historical wintering distributions could have been much wider, as whales were seen areas along Batanes, Sulu and Celebes Seas including off Palawan, Malaysia and Mindanao with higher densities at around today's Cape Eluanbi and Kenting National Park. Unconfirmed sightings have been reported near Borneo in Modern.

The first confirmation in modern Taiwan was of a pair off Hualien in 1994, followed by successful escape from entanglement off Taitung in 1999, and continuous sightings around Orchid Island in 2000. Few/none regularly migrate into Kenting National Park. In addition, despite sightings reported almost annually at the islands of Green and Orchid Islands, relatively short stays in these waters indicate recoveries as winter foraging has not occurred.

Around Hong Kong, two documented sightings were recorded in 2009 and in 2016. One of the first documented sighting within the Yellow Sea was of a group of 3 or 4 individuals,including a cow calf pair in Changhai County in October, 2015.

Since November 2015, whales gather around Hachijō-jima, far north from the known breeding areas in the Bonin Islands. All breeding activities except for giving births had been confirmed as of January, 2016. That makes Hachijo-jima the northernmost breeding ground in the world, north of breeding grounds such as Amami Ōshima, Midway Island, and Bermuda.

Arabian Sea population

A non-migratory population in the Arabian Sea remains there year-round. More typical annual migrations cover up to 25,000 km, making it one of the most-traveled mammalian species. Genetic studies and visual surveys indicate that the Arabian group is the most isolated of all humpback groups and is the most endangered, numbering possibly fewer than 100 animals.

Whales were historically common in continental and marginal waters such as Hallaniyat Islands, along Indian coasts, Persian Gulf and Gulf of Aden and recent migrations into the gulf including by cow-calf pairs. It is unknown whether whales seen in the Red Sea originate in this population,[89] however sightings increased since in 2006 even in the northern part of the sea such as in Gulf of Aqaba. Individuals may reach the Maldives, Sri Lanka, or further east.

Origins of whales occurring at Maldives are not clear as those from Arabian and south Pacific populations are possible.

Humpback whale range

Whale-watching

Whale watching is the leisure activity of observing humpbacks in the wild. Participants watch from shore or on touring boats. Humpbacks are generally curious about nearby objects. Some individuals, referred to as "friendlies", approach whale-watching boats closely, often staying under or near the boat for many minutes.

Because humpbacks are typically easily approachable, curious, identifiable as individuals and display many behaviors, they have become the mainstay of whale tourism around the world. Hawaii has used the concept of "ecotourism" to benefit from the species without killing them. This business brings in revenue of $20 million per year for the state's economy.

Whales are air-breathing mammals who must surface to get the air they need. The stubby dorsal fin is visible soon after the blow (exhalation) when the whale surfaces, but disappears by the time the flukes emerge. Humpbacks have a 3 m, heart-shaped to bushy blow through the blowholes.

They do not generally sleep at the surface, but must continue to breathe. Possibly only half of their brain sleeps at one time, allowing the other half to manage the surface/blow/dive process without awakening the other half.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Whale shark

Conservation status

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is a slow-moving filter feeding shark and the largest known extant fish species. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 12.65 m and a weight of about 21.5 t. Unconfirmed claims of considerably larger individuals, over 14 m long and weighing at least 30 t, are not uncommon.

The whale shark holds many records for sheer size in the animal kingdom, most notably being by far the largest living nonmammalian vertebrate. It is the sole member of the genus Rhincodon and the only extant member of the family, Rhincodontidae (called Rhiniodon and Rhinodontidae before 1984), which belongs to the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. The species originated about 60 million years ago.

The whale shark is found in open waters of the tropical oceans and is rarely found in water below 22 °C. Modeling suggests a lifespan of about 70 years, but measurements have proven difficult. They have very large mouths and are filter feeders, which is a feeding mode that occurs in only two other sharks, the megamouth shark and the basking shark. They feed almost exclusively on plankton and, therefore, are completely harmless to humans.

Whale sharks have a mouth that can be 1.5 m wide, containing 300 to 350 rows of tiny teeth and 10 filter pads which it uses to filter feed. Whale sharks have five large pairs of gills. The head is wide and flat with two small eyes at the front. Whale sharks are grey with a white belly. Their skin is marked with pale yellow spots and stripes which are unique to each individual. The whale shark has three prominent ridges along its sides. Its skin can be up to 10 cm thick. The shark has a pair of dorsal fins and pectoral fins. Juveniles' tails have a larger upper fin than lower fin, while the adult tail becomes semilunate. The whale shark's spiracles are just behind its eyes.

The whale shark is the largest non-cetacean animal in the world. The average size of adult whale sharks is estimated at 9.7 m and 9 t. Several specimens over 18 m in length have been reported The largest verified specimen was caught on 11 November 1947, near Baba Island, in Karachi, Pakistan. It was 12.65 m long, weighed about 21.5 t, and had a girth of 7 m.

Stories exist of vastly larger specimens – quoted lengths of 18 m and 45.5 t are common in the popular literature, but no scientific records support their existence. In 1868, the Irish natural scientist Edward Perceval Wright obtained several small whale shark specimens in the Seychelles, but claimed to have observed specimens in excess of 15 m, and tells of shark specimens surpassing 21 m.

In a 1925 publication, Hugh M. Smith described a huge animal caught in a bamboo fish trap in Thailand in 1919. The shark was too heavy to pull ashore, but Smith estimated the shark was at least 17 m long, and weighed around 37 t. These measurements have been exaggerated to 43 t and a more precise 17.98 m in recent years. A shark caught in 1994 off Tainan County, southern Taiwan, reportedly weighed 35.8 t. There have even been unverified claims of whale sharks of up to 23 metres and 100 tonnes.

In 1934, a ship named the Maurguani came across a whale shark in the southern Pacific Ocean, rammed it, and the shark became stuck on the prow of the ship, supposedly with 4.6 m on one side and 12.2 m on the other. No reliable documentation exists for these claims and they remain "fish stories".

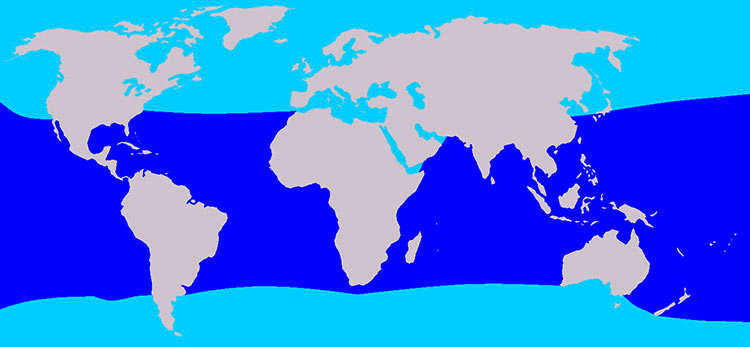

The whale shark inhabits all tropical and warm-temperate seas. The fish is primarily pelagic, living in the open sea but not in the greater depths of the ocean, although it is known to occasionally dive to depths of as much as 1,800 metres. Seasonal feeding aggregations occur at several coastal sites such as the southern and eastern parts of South Africa; Saint Helena Island in the South Atlantic Ocean; Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, Gladden Spit in Belize; Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia; Lakshadweep, Gulf of Kutch and Saurashtra coast of Gujarat in India; Útila in Honduras; Southern Leyte; Donsol, Pasacao and Batangas in the Philippines; off Isla Mujeres and Isla Holbox in Yucatan and Bahía de los Ángeles in Baja California, México; Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia; Cenderawasih Bay National Park in Nabire, Papua, Indonesia; Nosy Be in Madagascar Off Tofo Reef near Inhambane in Mozambique; the Tanzanian islands of Mafia, Pemba, Zanzibar; Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, the Ad Dimaniyat Islands in the Gulf of Oman and Al Hallaniyat islands in the Arabian Sea; and, very rarely, Eilat, Israel and Aqaba, Jordan.

Although typically seen offshore, it has been found closer to land, entering lagoons or coral atolls, and near the mouths of estuaries and rivers. Its range is generally restricted to about 30° latitude. It is capable of diving to depths of at least 1,286 m, and is migratory.

On 7 February 2012, a large whale shark was found floating 150 kilometres off the coast of Karachi, Pakistan. The length of the specimen was said to be between 11 and 12 m (36 and 39 ft), with a weight of around 15,000 kg

In 2011, more than 400 whale sharks gathered off the Yucatan Coast. It was one of the largest gatherings of whale sharks recorded. Aggregations in that area are among the most reliable seasonal gatherings known for whale sharks, with large numbers occurring in most years between May and september. Associated ecotourism has grown rapidly to unsustainable levels.

Whale Shark range

Behavior toward divers

Despite its size, the whale shark does not pose significant danger to humans. Whale sharks are docile fish and sometimes allow swimmers to catch a ride, although this practice is discouraged by shark scientists and conservationists because of the disturbance to the sharks. Younger whale sharks are gentle and can play with divers. Underwater photographers such as Fiona Ayerst have photographed them swimming close to humans without any danger.

The shark is seen by divers in many places, including the Bay Islands in Honduras, Thailand, the Philippines, the Maldives close to Maamigili (South Ari Atoll), the Red Sea, Western Australia (Ningaloo Reef, Christmas Island), Taiwan, Panama (Coiba Island), Belize, Tofo Beach in Mozambique, Sodwana Bay (Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park) in South Africa, the Galapagos Islands, Saint Helena, Isla Mujeres (Caribbean Sea), La Paz, Baja California Sur and Bahía de los Ángeles in Mexico, the Seychelles, West Malaysia, islands off eastern peninsular Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Oman, Fujairah, and Puerto Rico. Juveniles can be found near the shore in the Gulf of Tadjoura, near Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sperm whale

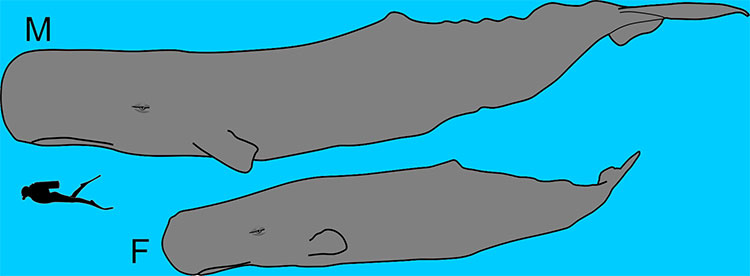

Size comparison of a male and female sperm whale with a human

(16m, 11m, 1.75m repsectively)

(16m, 11m, 1.75m repsectively)

Conservation status

Vulnerable

- IUCN Red List

of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Retrieved 7 October 2008.

Retrieved 7 October 2008.

The sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), or cachalot, is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of genus Physeter, and one of three extant species in the sperm whale family, along with the pygmy sperm whale and dwarf sperm whale of the genus Kogia.

Mature males average 16 metres in length but some may reach 20.5 metres , with the head representing up to one-third of the animal's length. Plunging to 2,250 metres, it is the second deepest diving mammal, following only the Cuvier's beaked whale. The sperm whale's clicking vocalization, a form of echolocation and communication, may be as loud as 230 decibels (re 1 µPa at 1 m) underwater. It has the largest brain of any animal on Earth, more than five times heavier than a human's. Sperm whales can live for more than 60 years.

The sperm whale can be found anywhere in the open ocean. Females and young males live together in groups while mature males live solitary lives outside of the mating season. The females cooperate to protect and nurse their young. Females give birth every four to twenty years, and care for the calves for more than a decade. A mature sperm whale has few natural predators, although calves and weakened adults are sometimes killed by pods of orcas.

From the early eighteenth century through the late 20th, the species was a prime target of whalers. The head of the whale contains a liquid wax called spermaceti, from which the whale derives its name. Spermaceti was used in lubricants, oil lamps, and candles. Ambergris, a waste product from its digestive system, is still used as a fixative in perfumes. Occasionally the sperm whale's great size allowed it to defend itself effectively against whalers. The species is now protected by a whaling moratorium, and is currently listed as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

Average sizes

The sperm whale is the largest toothed whale, with adult males measuring up to 20.5 metres long and weighing up to 57,000 kilograms. By contrast, the second largest toothed whale (Baird's Beaked Whale) measures 12.8 metres and weighs up to 14,000 kg.

The Nantucket Whaling Museum has a 5.5 metres long jawbone. The museum claims that this individual was 24 metres long; the whale that sank the Essex (one of the incidents behind Moby-Dick) was claimed to be 26 metres. A similar size is reported from a jawbone from the British Natural History Museum. A 20m specimen is reported from a Soviet whaling fleet near the Kuril Islands in 1950. There is disagreement on the claims of adult males approaching or exceeding 24 metres in length.

Extensive whaling may have decreased their size, as males were highly sought, primarily after World War II. Today, males do not usually exceed 18.3 metres in length or 51,000 kilograms in weight.

Another view holds that exploitation by overwhaling had virtually no effect on the size of the bull sperm whales, and their size may have actually increased in current times on the basis of density dependent effects. Old males taken at Solander Islands were recorded to be extremely large and unusually rich in blubbers.

It is among the most sexually dimorphic of all cetaceans. At birth both sexes are about the same size, but mature males are typically 30% to 50% longer and three times as massive as females.

The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped blowhole is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left. This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.

The sperm whale's flukes (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible. The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive. It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a dorsal fin. The largest ridge was called the 'hump' by whalers, and can be mistaken for a dorsal fin because of its shape and size.

In contrast to the smooth skin of most large whales, its back skin is usually wrinkly and has been likened to a prune by whale-watching enthusiasts. Albinos have been reported.

A map showing the distribution of sightings of sperm whales, based on the records of whalers and surveyors. Sperm whales can be found in virtually any part of the ocean not covered by ice, but are most often spotted in certain "grounds" where they like to feed or breed.

Map is centered on the Pacific (160° W). This map was made using GeoCart and data from http://seamap.env.duke.edu/species/180488

Map is centered on the Pacific (160° W). This map was made using GeoCart and data from http://seamap.env.duke.edu/species/180488

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Blue whale

Size comparison of an average human and a blue whale

Conservation status

Endangered (IUCN 3.1) IUCN Red List

of Threatened Species.

Version 2013.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

Version 2013.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a marine mammal belonging to the baleen whales (Mysticeti). At up to 30 metres in length and with a maximum recorded weight of 173 tonnes and probably reaching over 181 tonnes, it is the largest animal known to have ever existed.

Long and slender, the blue whale's body can be various shades of bluish-grey dorsally and somewhat lighter underneath. There are at least three distinct subspecies: Balaenoptera musculus musculus of the North Atlantic and North Pacific, Balaenoptera musculus intermedia of the Southern Ocean and Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda (also known as the pygmy blue whale) found in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean. Balaenoptera musculus indica, found in the Indian Ocean, may be another subspecies. As with other baleen whales, its diet consists almost exclusively of small crustaceans known as krill.

Blue whales were abundant in nearly all the oceans on Earth until the beginning of the twentieth century. For over a century, they were hunted almost to extinction by whalers until protected by the international community in 1966. A 2002 report estimated there were 5,000 to 12,000 blue whales worldwide, in at least five groups. The IUCN estimates that there are probably between 10,000 and 25,000 blue whales worldwide today. Before whaling, the largest population was in the Antarctic, numbering approximately 239,000 (range 202,000 to 311,000). There remain only much smaller (around 2,000) concentrations in each of the eastern North Pacific, Antarctic, and Indian Ocean groups. There are two more groups in the North Atlantic, and at least two in the Southern Hemisphere. As of 2014, the Eastern North Pacific blue whale population has rebounded to nearly its pre-hunting population.

Blue whale range (in blue)

Strandings

Blue whale strandings are extremely uncommon, and, because of the species' social structure, mass strandings are unheard of. When strandings do occur, they can become the focus of public interest. In 1920, a blue whale washed up near Bragar on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It had been shot by whalers, but the harpoon had failed to explode. As with other mammals, the fundamental instinct of the whale was to try to carry on breathing at all costs, even though this meant beaching to prevent itself from drowning. Two of the whale's bones were erected just off a main road on Lewis and remain a tourist attraction.

In June 2015, a female blue whale estimated at 12.2 meters and 20 tonnes was stranded on a beach in Maharashtra, India, the first live stranding in the region. Despite efforts by the Albaug forest department and local fisherman, the whale died 10 hours after being stranded. In August 2009, a wounded blue whale was stranded in a bay in Steingrímsfjördur, Iceland. The first rescue attempt failed, as the whale (thought to be over 20 meters long) towed the >20 ton boat back to shore at speeds of up to 7 miles per hour (11 km/h).

The whale was towed to sea after 7 hours by a stronger boat. It is unknown whether it survived. In December 2015, a live blue whale thought to be over 20 metres (65 feet) long was rescued from a beach in Chile. Another stranded blue whale, thought to be about 12.2 metres long, was rescued in India in February 2016. Boats were used in all successful cases.

Whale-watching

Blue whales may be encountered (but rarely) on whale-watching cruises in the Gulf of Maine and are the main attractions along the north shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and in the Saint Lawrence estuary. Blue whales can also be seen off Southern California, starting as early as March and April, with the peak between July and september. More whales have been observed close to shore along with fin whales.

In Chile, the Alfaguara project combines conservation measures for the population of blue whales feeding off Chiloé Island with whale watching and other ecotourism activities that bring economic benefits to the local people. Whale-watching, principally blue whales, is also carried out south of Sri Lanka. Whales are widely seen along the coast of Chile and Peru near the coast, occasionally making mixed groups with fin, sei, and Bryde's whales.

In Australia, pygmy blue and Antarctic blue whales have been observed from various tours in almost all the coastlines of the continent. Among these, tours with sightings likely the highest rate are on west coast such as in Geographe Bay and in southern bight off Portland. For later, special tours to observe pygmy blues by helicopters are organized.

In New Zealand, whales have been seen in many areas close to shore, most notably around the Northland coast, in the Hauraki Gulf and the Bay of Plenty, off South Taranaki Bight, in Cook Strait and off Kaikoura with remarkably increasing sighting trends in recent years with some whales started staying in the same area near the shore for several days. Similar approaches with Portland's case to use helicopters was once attempted in South Taranaki Bight, but seemingly been cancelled according to considerations.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

You are visitor no.

To www.aladdin.st since December 2005

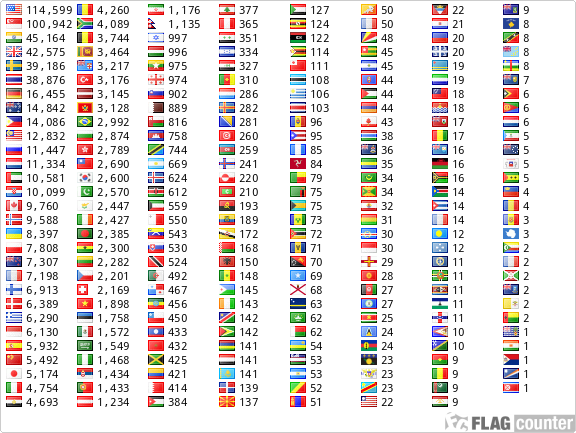

Visitors to www.aladdin.st from different countries since 26th of September 2011